Originally posted on 10/7/2018

Note: because this post was written in 2018, and some information in it has changed. For example, BTS now does get American radio play for their songs (though only the ones they recorded in English), their fanbase is much, much larger, and many of their music videos now average 1 billion views. I keep the information unaltered here because it is about a specific moment in their trajectory as a group and pop music phenomenon. Please enjoy!

Here is a moment I think I will remember for the rest of my life: as we were driving to NYC to see the most famous boyband in the world, K-pop group BTS, one of my best friends got a text alert that Brett Kavanaugh had been confirmed to a lifetime appointment on the Supreme Court.

The timing was, if anything, surreal. I have had these tickets for almost two months, but never would have imagined this show would coincide with this particularly hellish development in the news. But truthfully, many things about this trip were unexpected. When, a little over four months ago, I chanced upon a BTS video on YouTube after seeing a short Netflix documentary on K-pop, I had no idea it would lead to making a trip like this to a sold-out show at Citi Field, the 40,000 person capacity Mets stadium. The concert is historic: no Asian band has ever played a stadium show in the US. The BTS show sold out in under ten minutes.

I remember the fateful moment I watched that music video. I was at the tail end of a writing retreat that had not gone particularly well, sequestered in a strange Air Bnb in western PA where it’s really West Virginia – full-on Trump country. The video was for their song “Blood, Sweat and Tears,” and came out several years ago. It’s gorgeous and cinematic, as are many K-pop videos, but also more than vaguely sinister. The song is an innocuous dance bop about unhealthy relationships, maybe a little minor-sounding, but the aesthetic is Interview with a Vampire meets Alice in Wonderland meets Phantom of the Opera. There’s some light bondage. There’s an interlude in which they quote Herman Hesse and show one member kissing a winged statue while another reveals the scars on his back from where he’s lost his wings. To quote my friend Lisa, who bravely agreed to go with me to this show, “I don’t understand it, but I love it.”

Watching that video in that part of Pennsylvania felt fairly deviant. Despite being the product of an intensely patriarchal and fairly conservative South Korean society, K-pop is undeniably influenced by two types of cultural rebellion: hip-hop and queerness. These are also the most important cultural influences in my life, and so I think, though it took me awhile to get here, that in some ways K-pop and I were destined to meet.

Though I did not know it until I got to the concert itself, BTS’s fanbase is not only worldwide (estimated at somewhere around 15 million strong) it is also incredibly diverse. I don’t think I’ve ever been to a more diverse concert, in fact. So many races and hair colors and aesthetics and ages. It makes sense to me, because BTS’s music is not only engaging on that extremely accessible pop level, their message is one of complete inclusivity. Their last three albums have been part of a series entitled “Love Yourself,” and their unequivocal message can be summed up in this way: before we know how to love others, we must give that same love and acceptance to ourselves. This is an interesting message for a pop group to put forth, especially considering that their fans are predominantly young women and queer people. In the age of Trump and Kavanaugh, this is not the message we are sending to young people, or frankly – to anyone who is not a cisgender wealthy white straight male.

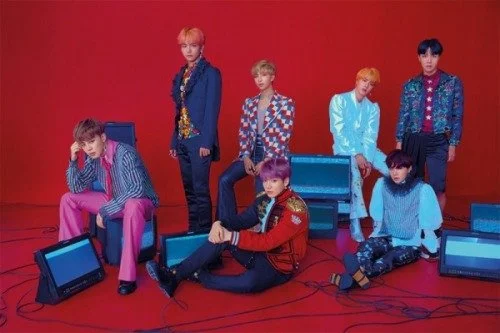

Being in a crowd of 40,000 people dancing and yelling and singing along to lyrics about loving who you are no matter what people say about you felt like a rebellion in the same way watching that music video did, except multiply that feeling by one million. BTS may be adorable and fun to dance to, but they are not apolitical. At various points, BTS’s songs call out parents and other adults for putting young people in a pressure cooker that doesn’t yield the opportunities they’ve been told to strive for. They call out their haters for saying they aren’t real musicians because they make dance music. They call out people who shit on you because you struggle with mental illness. They call out their government for being misleading and corrupt. They wear costumes that call to mind queer pop icons like Prince and David Bowie and Elton John. There is so much leather and sheer fabrics and flowers and sparkle. They are androgynous but also represent a soft sort of masculinity, and are visibly affectionate with each other with absolutely no self-conscious no-homo vibes. Their dancing is both remarkably precise and incredibly joyous. And they thank their fans. Over. And Over. And Over again.

Interestingly enough, the story of BTS in America is one of subversion of the American music industry itself. Though they don’t get radio play and rarely appear on American TV, many of their music videos have over 300 million views, with America being the third largest source of watchers. All of their North American shows sold out in minutes with no on-the-ground promotion. They debuted at #1 on the Billboard charts despite the fact that their music is almost entirely in Korean. They are in themselves a fuck-you to an industry that has always insisted that Americans won’t consume entertainment from around the world.

From a purely cynical point of view, BTS playing Citi Field is an enormous victory for the Kpop industry, which has always had its eye on the xenophobic US market as its ultimate goal. But it is also an enormous personal victory for the seven young men who have spent the last eight years of their lives getting here. This was clear in the final moments of the show, when each member gave carefully prepared remarks – some in English, some in Korean with an interpreter – saying how grateful they were to be there. “You are the brightest stars in my universe,” one said, while another dissolved into tears and could not keep going. Their leader RM, the only member fluent in English, gave a small speech which ended with: “What is loving myself? What is loving yourself? I don’t know. Who can define their own method and the way of loving myself? It’s our mission to define our way to love ourselves. So, it’s never intended, but it feels like I’m using you guys to love myself. I want to say one thing: please, please use me. Please use BTS to love yourself. Because you guys taught me how to love myself.”

This is some heavy stuff for a pop concert, but hearing it felt like – for that one moment – a weight had been lifted. While I despair about the news cycle, I am not afraid for our future. Most of the work I do is with or for young people, and I see a generation that is so much more accepting and embracing of difference, so much less afraid to be who they are. As much as it may seem like a leap, BTS is part of that. In a speech they gave at the UN’s General Assembly a few weeks ago, they encouraged all people to speak their stories, to feel validated, and to believe they can do good in the world. Such rhetoric would not be out of place at an Obama rally. The difference is that they have the ears of the young people who will shape this world. And for those hundreds of thousands that have seen them at sold-out shows in the last few months, they are unlikely to forget the experience.

I know I won’t.